I’ve looked at a lot of triangle-triangle intersection code across different projects. And every time, one thing stood out: there’s no single implementation that covers all the edge cases.

That’s not surprising. The requirements vary wildly depending on the use case – fast-and-loose for games, watertight for CAD, approximated for physics engines. But in this post, I’ll describe a method that is as general and precise as possible – something robust enough for CAD systems.

The narrative will follow the tone and structure of the earlier post – Is the Point Inside the Triangle? If you haven’t read it, I suggest doing so first – it’ll make everything that follows here feel much more intuitive. Moreover, I recommend opening the post in a separate tab so that you can quickly refer to it.

Goals of this post

- To demonstrate how much easier this post is to follow if you’ve read the first one.

- To share another excerpt from the book I’m writing.

The algorithm has two phases:

Phase 1

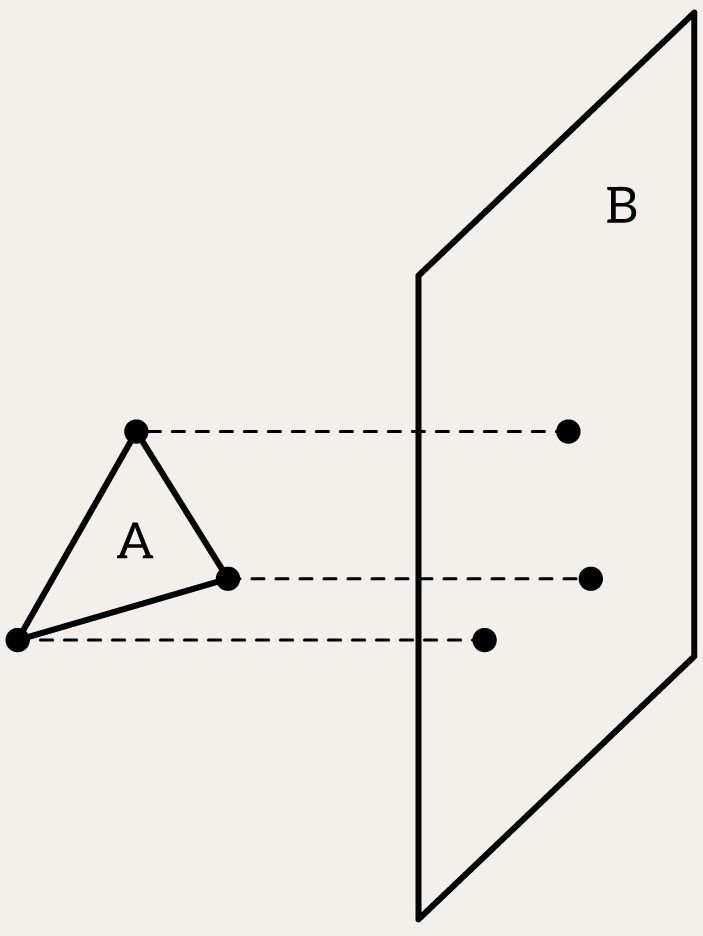

If all three vertices of triangle B lie on the same side of the plane (either all on the positive side or all on the negative side), then triangle B does not intersect the plane of triangle A.

Otherwise, swap A and B and repeat above.

This is a cheap early exit. There’s no point in performing an expensive intersection check if one triangle lies entirely on one side of the other triangle’s plane.

auto isTriangleCompletelyOnOneSide = [](Plane plane, Triangle triangle, double epsilon) {

return calculateNumberOnPositiveSide(plane, triangle, epsilon) == 3 ||

calculateNumberOnNegativeSide(plane, triangle, epsilon) == 3;

};

if (isTriangleCompletelyOnOneSide(createPlaneFromTriangle(B), A, epsilon) ||

isTriangleCompletelyOnOneSide(createPlaneFromTriangle(A), B, epsilon))

return false;

createPlaneFromTriangle is just a wrapper around createPlane, from the first post:

[[nodiscard]] Plane createPlaneFromTriangle(Triangle triangle) {

glm::dvec3 N = glm::cross(triangle.V1 - triangle.V0, triangle.V2 - triangle.V0);

return createPlane(triangle.V0, N);

}

Note that the other functions like isPointInsideTriangle also has overloads that accept triangle structure:

[[nodiscard]] bool isPointInsideTriangle(glm::dvec3 P, Triangle triangle, double epsilon) {

return isPointInsideTriangle(P, triangle.V0, triangle.V1, triangle.V2, epsilon);

}

Also note that I introduced a Triangle data structure, which is simply a struct with three vertices: V0, V1, and V2. There’s a common misuse where someone introduces operator[](size_t index) to access a vertex by index. I believe this practice is misleading because it gives the impression that you can index beyond 0 to 2, or that indexing might be cyclic, for example.

Phase 2

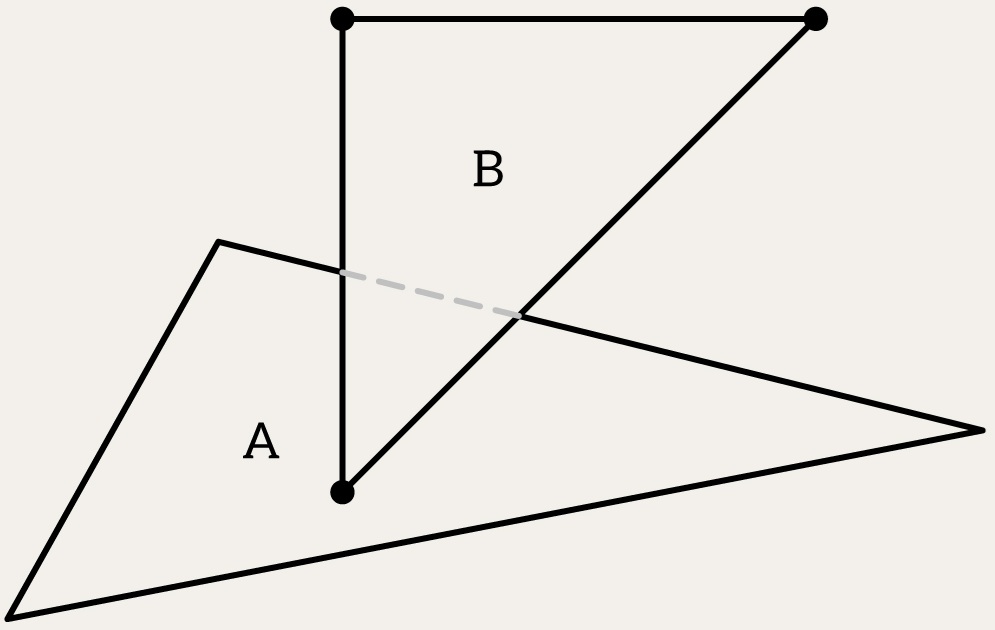

- Then, we check whether any edge (or vertex) of triangle B touches the plane of triangle A

- Then, we check whether any edge (or vertex) of triangle B intersects the plane of triangle A

- Then, we swap A and B and repeat the above

This guarantees that all types of intersections – partial overlaps, shared edges, or even single-point contact – are detected. The good news is that if you’ve already implemented the point-in-triangle test from the previous post, you’re halfway there. The rest is about reasoning with segments, lines, and their relation to the plane of a triangle. Let’s build those, step by step.

[[nodiscard]] bool intersects(Triangle A, Triangle B, double epsilon) {

for (auto seg : { Segment(B.V0, B.V1), Segment(B.V1, B.V2), Segment(B.V2, B.V0) })

if (intersects(seg, A, epsilon))

return true;

return false;

}

Therefore, the second phase looks like this:

if (!intersects(A, B, epsilon) && !intersects(B, A, epsilon))

return false;

Edges as Segments

We start by defining an edge of a triangle as a segment – a straight connection from point source to point target:

struct Segment {

glm::dvec3 source;

glm::dvec3 target;

};

Now we want to be able to evaluate any point along this segment. This is where a familiar concept (see barycentric section from the first post) returns – the parameter t.

[[nodiscard]] glm::dvec3 pointOnSegmentAtParam(Segment segment, double t) {

return glm::lerp(segment.source, segment.target, t);

}

Note the [[nodiscard]] attribute. I wish all functions in C++ were marked [[nodiscard]] by default – this is especially important for math routines. But it is what it is.

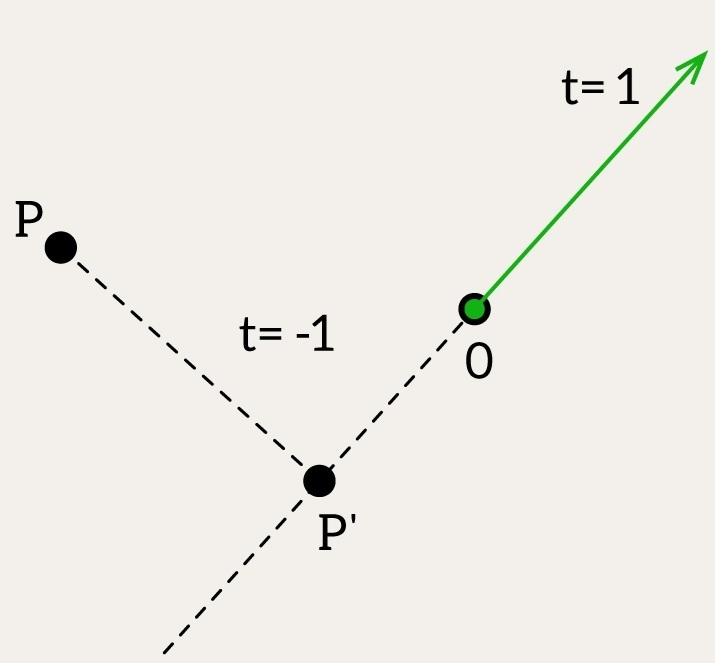

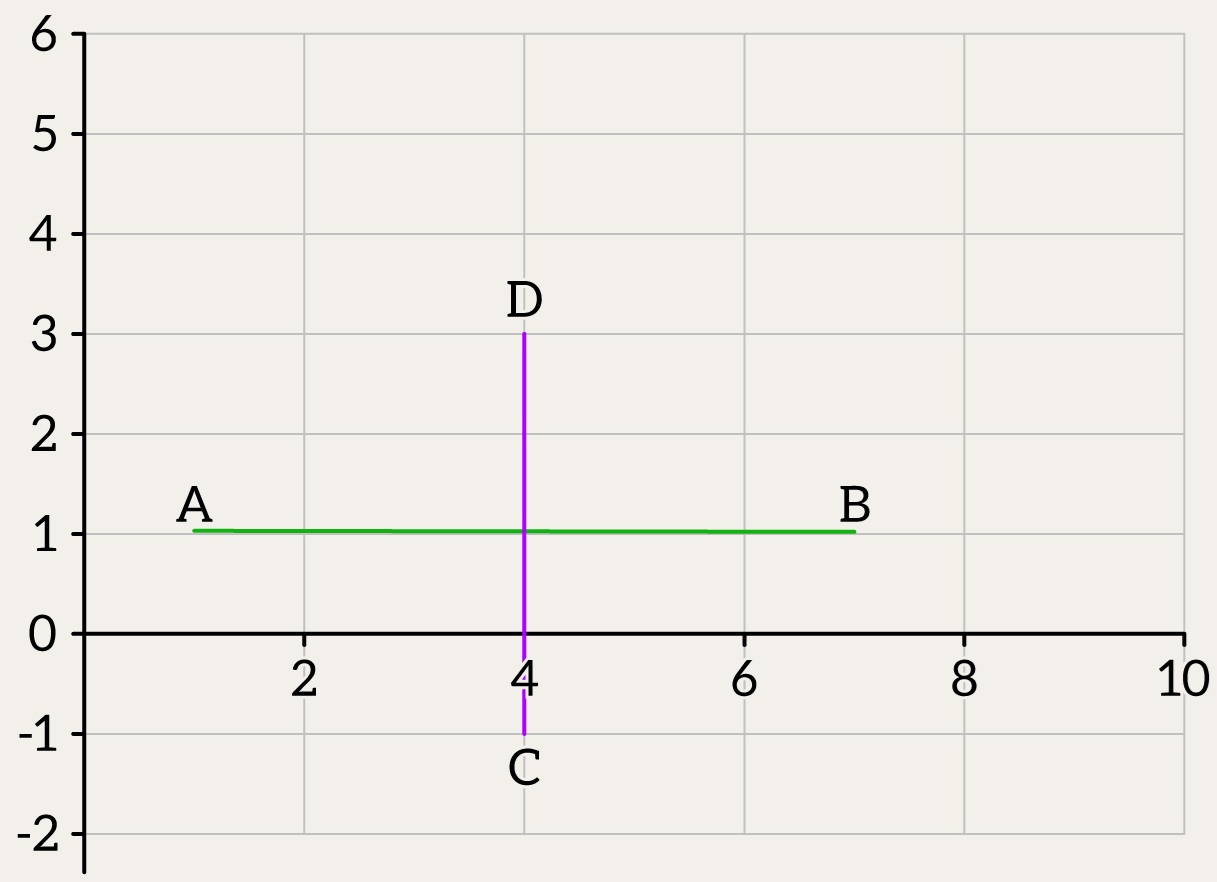

Digression 1: What is t Intuitively?

In the previous post, we introduced barycentric coordinates for triangles – weights that tell us how much influence each point has in defining a position. The parameter t plays a similar role here, but in one dimension.

Think of t as a slider between 0 and 1:

- At

t = 0, you’re exactly at the start point. - At

t = 1, you’ve reached the end. - At

t = 0.5, you’re in the middle – balanced between source and target.

In a way, t is time. If you start walking from point A toward point B and arrive at t = 1, then t tells you how far along the journey you are.

This same logic will extend to lines, rays, and projections.

From Segment to Line

Sometimes, we want to reason not just about the finite edge, but about the infinite extension in both directions. This brings us to the concept of a line:

struct Line {

glm::dvec3 origin;

glm::dvec3 dir;

};

A line is defined by a starting point origin and a direction vector dir. To construct a line from two points:

[[nodiscard]] Line createLineFromTwoPoints(glm::dvec3 A, glm::dvec3 B) {

return {A, B - A};

}

We’ll now extend our intuition for t to this line.

[[nodiscard]] glm::dvec3 pointOnLineAtParam(Line line, double t) {

return line.origin + line.dir * t;

}

Now t is no longer limited to the 0, 1 range.

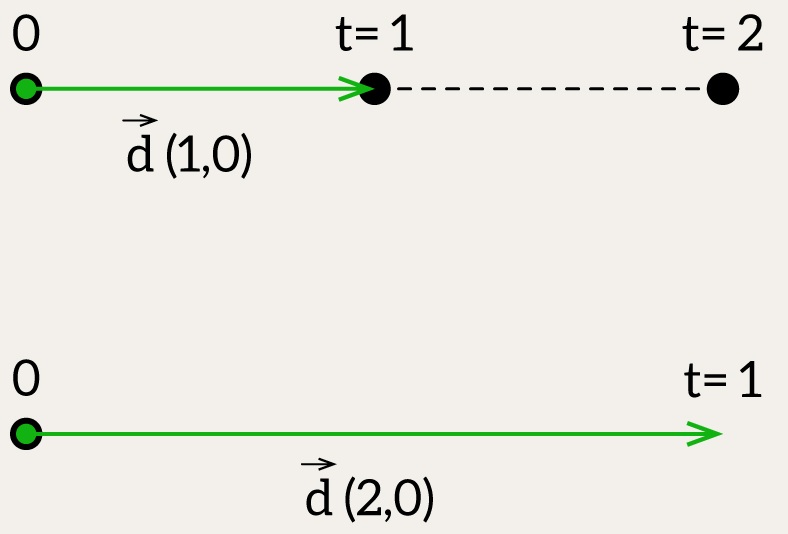

Digression 2: Continuing with t for lines

When working with a Line, you can evaluate points far beyond the original segment:

t = 5means five units in the direction ofdirt = -2means two units against the direction ofdir

But here’s an important detail: the meaning of “unit” depends entirely on the length of dir. If dir is normalized (i.e., its length is 1), then t = 5 really means five units of distance. But if dir is, say, (2, 0, 0), then t = 1 already moves you two units along the X-axis. Or, to put it another way – you’re living in a world where one unit of local distance equals two global units. Your measuring stick is just… longer.

So in that case:

t = 1→(origin + (2, 0, 0))t = 2→(origin + (4, 0, 0))

Effectively, each step of t is scaled by the magnitude of dir. If you want t to represent actual distance, you’ll need to normalize dir.

Whether you keep dir normalized or not depends on context.

For intersections and projections, unnormalized vectors often make things simpler (no square roots!). But for measuring physical distance or stepping evenly, normalization becomes essential.

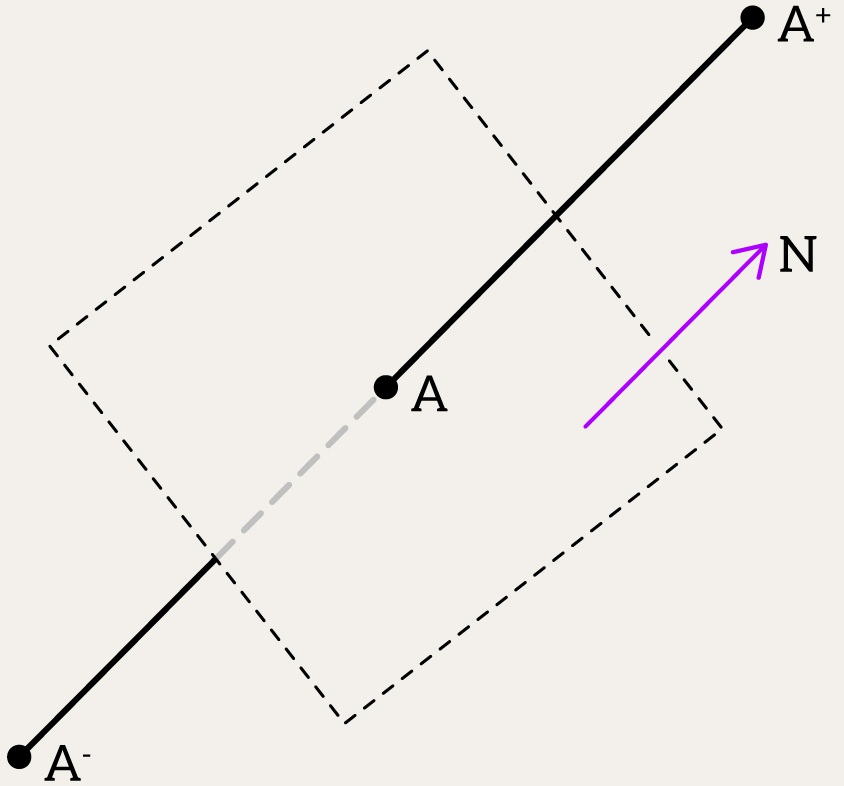

Projecting a Point onto a Line

Now let’s say you need to solve the opposite problem – find a parameter t given a line and a point P. We want to know: If I drop a perpendicular from P to the line, where does it land? How far along the line is that?

This is where the parameter t becomes useful – not as a description of P directly, but of its projection onto the line. Here’s how we compute it:

[[nodiscard]] double parameterAlongLine(Line line, glm::dvec3 P) {

glm::dvec3 vec = P - line.origin;

return glm::dot(vec, line.dir) / glm::dot(line.dir, line.dir);

}

The formula is very simple: we know that the closest point lies along the perpendicular to the line, which means – as we know from the previous post – that dot(P - P', d) must be 0. We also know that the point P' is origin + t * d; from there, we solve for t.

Or another intuitive explanation: How much does vec “point” in the same direction as dir? dot(vec, dir) is like the shadow of vec onto dir, but it’s not yet normalized. To get the actual length of that shadow, in the “units” of dir, you need to divide by the squared length of dir.

What this returns is the scalar t such that:

[[nodiscard]] glm::dvec3 projectPointOntoLine(glm::dvec3 P, Line line) {

double t = parameterAlongLine(line, P);

return pointOnLineAtParam(line, t);

}

So what does t mean if P is not on the line?

It still tells you how far – and in which direction – you’d have to move along the line from origin to reach the closest point to P on that line.

Geometric Intuition

- If

t = 0: the projection ofPlies exactly atorigin. - If

t = 1: it’s one fulldirvector away fromorigin. - If

t = 0.5: halfway. - If

t < 0: the projection lies behind the origin. - If

t > 1: it lies beyond the point reached bydir.

This is true even if P is floating somewhere far from the line – the value of t always describes the foot of the perpendicular from P to the line.

And that’s very powerful: even when P is off in space, t still gives us a clear reference point on the line – and that’s what allows us to detect nearest points, distances, and intersections.

Is the Point on the Line?

Projection gives us a candidate location. But we still need to check: does P actually lie on the line? To confirm this within floating-point tolerance, we project and compare:

[[nodiscard]] bool isPointOnLine(glm::dvec3 P, Line line, double epsilon) {

glm::dvec3 projectionPoint = projectPointOntoLine(P, line);

return equals(projectionPoint, P, epsilon);

}

Where equals() is a function you define to check proximity in all dimensions using a small epsilon.

Is the Point on the Segment?

Lines are infinite. Segments are not. To verify whether P lies within the segment (note that I deliberately left the code unoptimized for clarity):

[[nodiscard]] bool isPointOnSegment(glm::dvec3 P, Segment segment, double epsilon) {

Line line = createLineFromSegment(segment);

double lengthSquared = glm::dot(line.dir, line.dir);

// Handle degenerate segment (almost zero length)

if (lengthSquared < epsilon * epsilon)

return glm::length2(P - line.origin) < epsilon * epsilon;

// Compute projection parameter t

double t = parameterAlongLine(line, P);

// Check if the projection lies within the segment bounds

if (t < -epsilon || t > 1.0 + epsilon)

return false;

return isPointOnLine(P, line, epsilon);

}

All this stuff is quite boring – you just use dot or cross products or sometimes both of them. 🙂

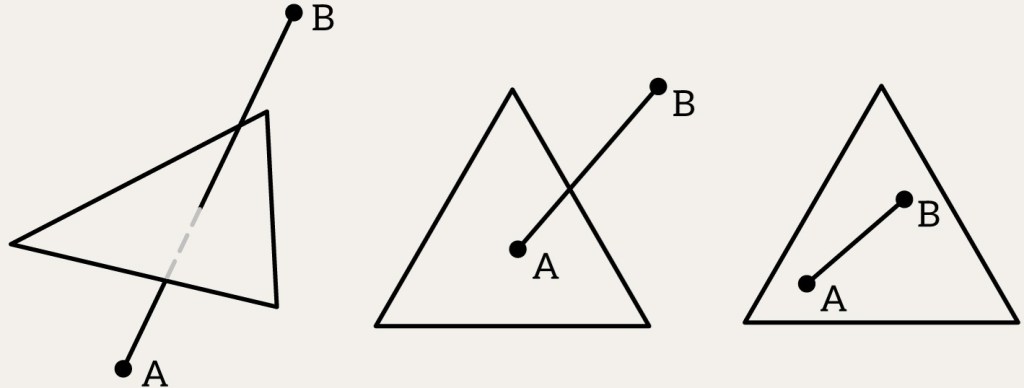

Check if Segment intersects Triangle

Finally, we arrive at the second stage of the algorithm –

“Then, we check whether any edge (or vertex) of triangle B intersects/touches the plane of triangle A.”

To determine whether a segment intersects a triangle, we begin by constructing the plane of the triangle and checking whether the segment intersects that plane. Only if it does, we proceed to more detailed checks.

As described in the Is the Point Inside the Triangle post, we start by building the plane from the triangle.

Plane plane = createPlaneFromTriangle(triangle);

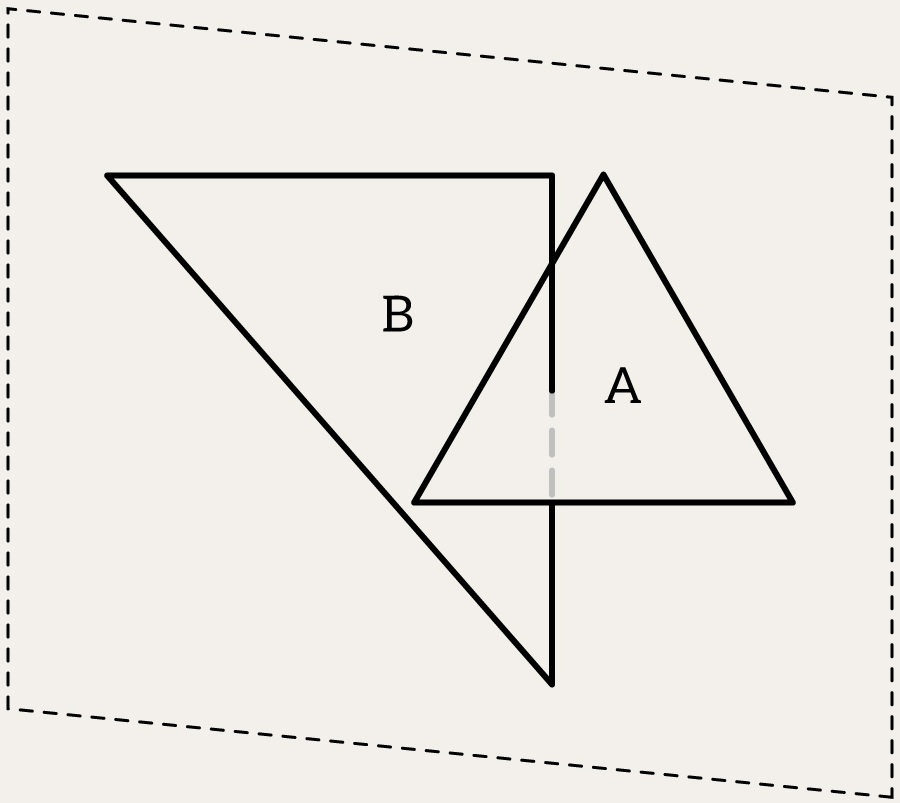

Unlike lines, segments have clear endpoints, and so the intersection can be:

- a single point (if the segment pierces the plane or touches the plane),

- a coincidence (if the whole segment lies on the plane),

- or no intersection at all (if the segment lies entirely on one side).

So all we need is just to reason about all possible cases of segment vertices against the plane.

enum class PlaneSide { Negative, OnPlane, Positive };

[[nodiscard]] PlaneSide sideOfPlane(Plane plane, glm::dvec3 point, double epsilon) {

double distance = glm::dot(plane.N, point) + plane.D;

if (std::abs(distance) <= epsilon)

return PlaneSide::OnPlane;

return distance > 0.0 ? PlaneSide::Positive : PlaneSide::Negative;

}

The final function for checking the intersection between a plane and a segment looks like this:

[[nodiscard]] std::variant<std::monostate, Point, Segment> findPlaneSegmentIntersection(Plane plane, Segment segment, double epsilon)

{

PlaneSide sourceSide = sideOfPlane(plane, segment.source, epsilon);

PlaneSide targetSide = sideOfPlane(plane, segment.target, epsilon);

// check all combinations

}

Case Breakdown:

sourceSide | targetSide | Result | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| OnPlane | OnPlane | Segment | Entire segment lies on the plane |

| OnPlane | Negative | Point = source | Intersection at source point |

| OnPlane | Positive | | Intersection at source point |

| Positive | OnPlane | Point = target | Touches plane at target point |

| Positive | Negative | Point (computed) | Crosses plane |

| Positive | Positive | | No intersection – both points on same side |

| Negative | OnPlane | Point = target | Touches plane at target point |

| Negative | Negative | | No intersection – both points on same side |

| Negative | Positive | Point (computed) | Crosses plane |

In cases where the segment intersects the plane, we:

- Convert the

segmentinto aline - Substitute the line equation into the plane equation and solve for

t - Use

tto compute theintersection point

And then we need to decide what to do with the result. There are three possible outcomes: No intersection, Point, Segment.

[[nodiscard]] bool intersects(Segment segment, Triangle triangle, double epsilon) {

Plane plane = createPlaneFromTriangle(triangle);

auto result = findPlaneSegmentIntersection(plane, segment);

if (std::holds_alternative<std::monostate>(result))

return false;

if (const auto* point = std::get_if<glm::dvec3>(&result)) {

// point case

}

if (const auto* seg = std::get_if<Segment>(&result)) {

// segment case

}

return false;

}

Point. If the result of intersection between plane and segment is point then you need to check if point lies on the triangles boundary. In order to do that you need to check three edges (segments) of triangle and check if point lie on any one of them. You already know how to check it. And of course you need to check if point lies inside triangle – see, well, you know, post 1.

for (auto seg : { Segment(tr.V0, tr.V1), Segment(tr.V1, tr.V2), Segment(tr.V2, tr.V0) })

if(isPointOnSegment(point, seg, epsilon))

return true;

return isPointInTriangle(point, tr, epsilon);

Segment. Almost the same as for point case – you need to check if source and target of segment lie on triangles boundary. Then, it’s the most interesting case – check if segment intersects one of the triangle edge – basically checking intersection between two segments.

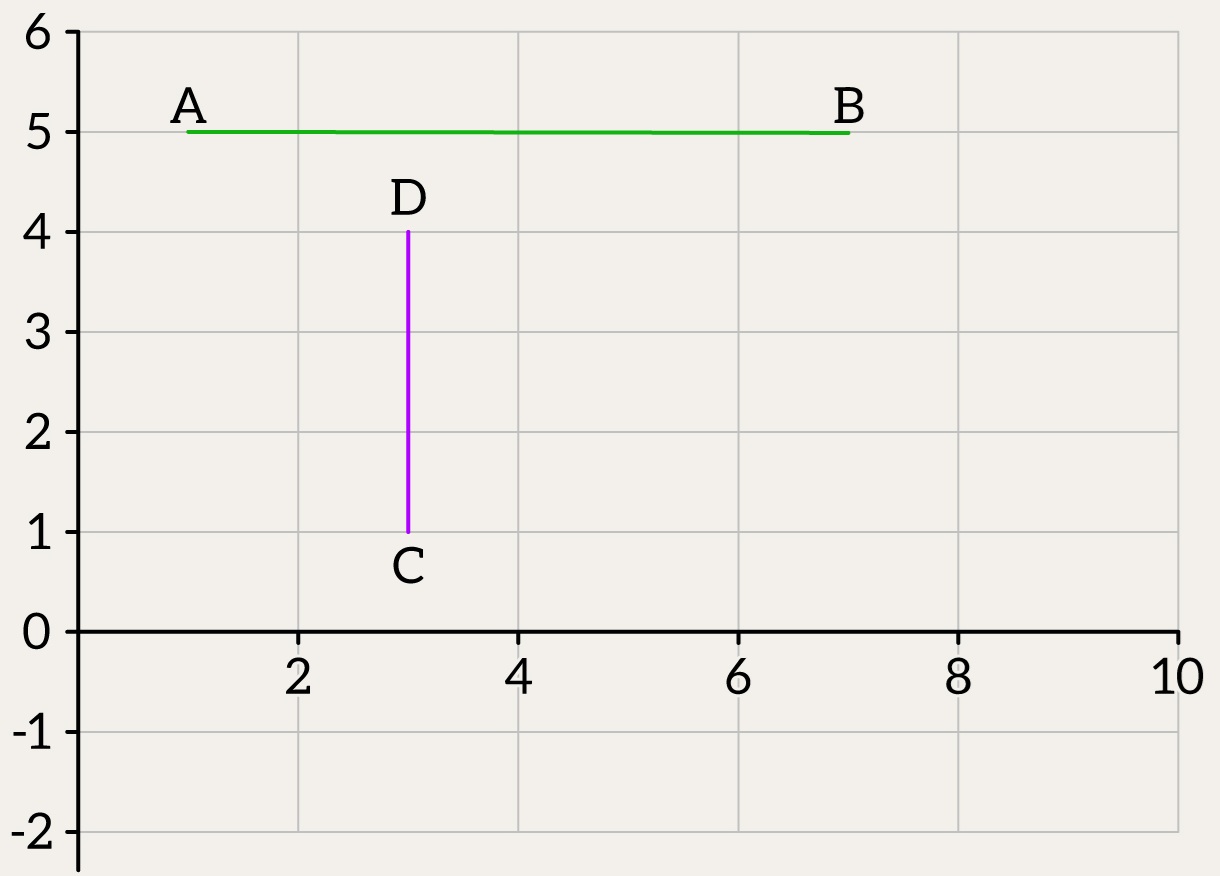

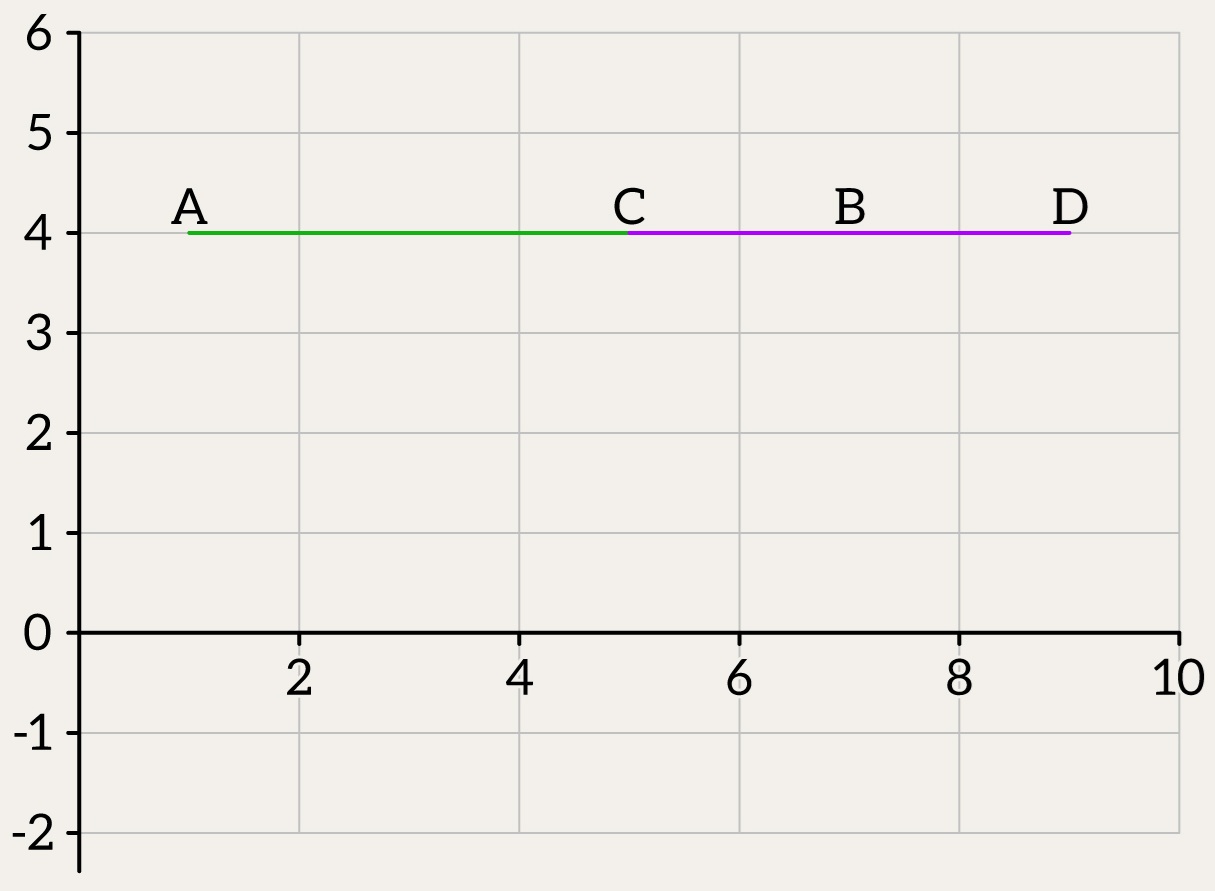

Intersection between two segments

Let’s do the trick we used in the first post (again) – let’s drop the coordinate with the maximum value and transform our 3D problem into a 2D problem.

Then we’ll have exactly the same logic as we did with planes: we treat each segment as a line and check on which side of that line the endpoints of the other segment lie. If the endpoints lie on opposite sides, the segments may intersect; if on the same side, they do not intersect. If any point lies exactly on the line, we additionally check whether it lies on the actual segment.

Line2 is just like a plane, but in 2D – it represents a line using the implicit equation N·P + C = 0. Here, N is the normal vector of the line (pointing perpendicular to it), and C is an offset that shifts the line in space. Just like with a plane equation in 3D, this form makes it easy to check which side of the line a point is on, or how far it is from the line.

struct Line2 {

glm::dvec2 N;

double C;

};

enum class LineSide { Negative, OnLine, Positive };

[[nodiscard]] LineSide sideOfLine(Line2 line, glm::dvec2 P, double epsilon) {

double distance = glm::dot(line.N, P) + line.C;

if (std::abs(distance) <= epsilon)

return LineSide::OnLine;

return distance > 0.0 ? LineSide::Positive : LineSide::Negative;

}

Next, we simply do reasoning about possible outcomes.

Case | Condition | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Both endpoints of seg1 on same side of seg2’s line | Both endpoints of seg1 lie strictly on the same side of seg2’s supporting line | No intersection |

| Both endpoints of seg2 on same side of seg1’s line | Both endpoints of seg2 lie strictly on the same side of seg1’s supporting line | No intersection |

| Main case: strict intersection | Endpoints of both segments lie on opposite sides of each other’s line | Strict intersection |

| Degenerate case: touching or colinear overlap | Segments touch at a point or overlap while being colinear | Touching / Overlap |

And that’s actually it.

What you can optimize – and what I intentionally did not do here (for clarity) – is:

- you can reuse planes in the code

- you can reuse computed distances from points to planes,

- and, of course, you can add cheap early checks – for example, checking whether two points lie on the plane, or whether they are on opposite sides of the plane, before calling the full intersection check between the triangle and the segment.

And that’s it – no magic, just some careful math and a few well-placed optimizations. 🙂

Leave a comment